Maybe "The Green Mile" is cosmic payback for all the lousy movie adaptations Stephen King's fans have had to put up with over the years. You can raise all kinds of legitimate objections to Frank Darabont's film of King's sweeping fable about an ambiguous, even tragic miracle that comes to death row in a Louisiana prison in 1935 -- and, at a running time of three full hours, it will certainly test holiday audiences' gluteus muscles. But this is six-Kleenex Hollywood melodrama of the highest order, a sumptuously appointed fantasy with a core of genuine honesty and sadness. Yes, it's preachy and moralistic, and it uneasily blends childish whimsy on one hand with cruel horror on the other. These have been the qualities of popular storytelling since prehistory, and "The Green Mile" is above all a cracking good yarn that earns its laughter, its wonder and its tears.

By most calculations, King is the biggest-selling novelist in the history of publishing. But his work has translated to film with surprisingly indifferent results, in both artistic and commercial terms. If you exclude the highly individual interpretations of Brian De Palma's "Carrie," Rob Reiner's "Stand by Me" and Stanley Kubrick's "The Shining," most of the 49 King adaptations made for film and television (that's right!) have faded into forgettable cinematic wallpaper, formula fare for night-owl cable viewers. (OK, we should also make allowances for Kathy Bates' star turns in Reiner's "Misery" and Taylor Hackford's "Dolores Claiborne.") As for the horror-meister's lone foray into directing his own work, the 1986 truck-monster saga "Maximum Overdrive," the less said the better.

It often seemed that the movies didn't get King on some fundamental level. His plots could be boiled down to 90 minutes readily enough, but in so doing you lost the tone of 19th-century corn pone melodrama and the anguished moralizing that are so central to the experience of King's mammoth tomes. Too many filmmakers think only about the way things look and the way they work rather than what they mean, and they failed to notice that King's horror is not really about undead children, haunted hotels or rabid dogs but human misery. But when Darabont, then a little-known writer and director whose credits included screenplays for "The Fly II" and "A Nightmare on Elm Street 3," adapted King's short story "Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption" in 1994, everything changed.

Darabont's smashing success directing Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman as resilient lifers in "The Shawshank Redemption" marked the first time King's sentimental sweep, leisurely pace and grandiose symbolism had really made it from page to screen intact. I suppose the period prison setting and similarly melancholic tone of "The Green Mile" made Darabont the obvious choice, but it's a much tougher challenge than "Shawshank," and the filmmaker has risen to it handsomely.

It helps that "The Green Mile" is among the most overtly cinematic of King's larger works, and that the author used its unorthodox form to free himself from some of his more tiresome mid-career obsessions. Published in six paperback installments in 1996 -- in an apparent tribute to the serial-novel tradition popularized by King's hero, Charles Dickens -- "The Green Mile" moves a long way from King's customary Maine setting and avoids his '90s pseudo-feminism. It even has a strong suggestion of religious allegory, a topic King stringently avoided in his earlier work.

Inevitably, Darabont has stripped King's present-day narrative, in which retired prison guard Paul Edgecomb (veteran character actor Dabbs Greer), confined to a nursing home and troubled by nightmares, begins to reflect on what he witnessed 60 years earlier, down to the barest of framing devices. This robs the film's conclusion -- when we learn the truth about why Paul finds himself so alone in the 1990s -- of some of its pathos, but at least allows Darabont to pack in most of the crucial details of the '30s story.

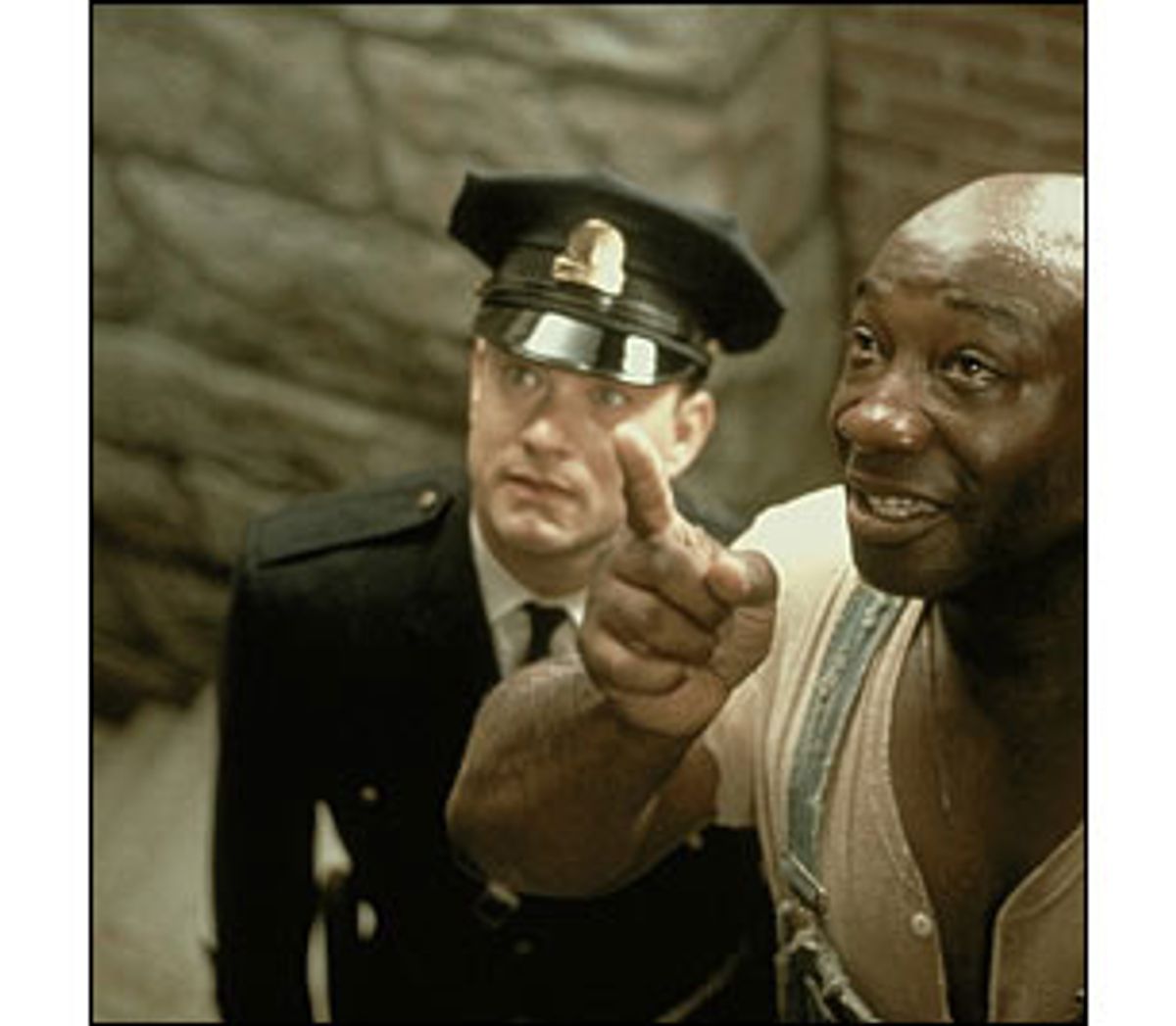

As chief guard for E Block at Cold Mountain prison, where condemned men wait to walk the pale green corridor toward the electric chair, the younger Paul (Tom Hanks) is a good man in an evil situation -- a classic dilemma for a melodramatic hero. As tired as I am of Hanks' roles as models of rock-stolid American rectitude, his boyish yet middle-aged good looks are perfect here; Paul is the moral linchpin around whom the grotesquerie of "The Green Mile" swirls. He runs a tight ship, treating both his subordinates and prisoners with respect and dispatching the latter to the next world with a minimum of fuss. Paul's men, especially his genial lieutenant whose ironic nickname is Brutal (David Morse), follow his lead. Brutality and abuse are not countenanced on the Green Mile.

If it seems far-fetched to imagine a group of white death-row guards in the Depression-era deep South as upstanding citizens virtually devoid of bigotry or hatred, I would argue that King is stretching plausibility to make a crucial point: The Green Mile is a place where even the best men do bad things. There's no explicit ideology about racism or capital punishment in this movie, but there's also no mistaking the thickening atmosphere of tangible menace, sadism and fear that Darabont so effectively builds. The three grueling electrocution scenes in "The Green Mile" should do more to sour its viewers on the death penalty than any number of earnest magazine articles -- don't bring your kids (or yourself) to this movie expecting sugary clichis about the nobility of death.

The cast of characters who meet on the Green Mile in 1935 create a volatile brew that even the phlegmatic Paul cannot control. Guards and prisoners alike come straight out of the Victorian penny dreadful tradition. Percy Wetmore (Doug Hutchison), a cocky young guard with a mean streak, plans to use his state government connections to ensure he personally supervises an execution. John Coffey (Michael Clarke Duncan), a hulking black man convicted of raping and murdering two white girls, is a sensitive, simple-minded soul who cries in his cell at night. Eduard Delacroix (Michael Jeter), a Cajun prisoner whose execution is drawing near, has trained a remarkable pet mouse named Mr. Jingles, who seems mysteriously able to evade capture. Wild Bill (Sam Rockwell), a vicious, unrepentant killer with a redneck swagger, assaults the guards, trashes his cell and provokes conflict at every opportunity.

Managing this outstanding cast and the almost luscious photography of David Tattersall with a sure hand, Darabont refuses to be rushed, giving each of these characters -- even the irresistible Mr. Jingles -- enough time for us to invest in them. (Hating a character, as you will undoubtedly hate Percy and Wild Bill, is after all a form of caring about him.) Even the most problematic character, the gentle giant Coffey, who sometimes borders on offensive racial caricature in King's book, becomes a flesh-and-blood human being in Duncan's dignified and sensitive portrayal. On the other hand, the film's compressed plot means that Coffey's apparent powers to heal the sick and punish the wicked -- and hence his possible resemblance to another condemned man with the same initials -- come into focus much more quickly, while Paul's efforts to learn the story behind Coffey's crime seem rather cursory.

From Coffey's near-erotic ability to suck illness from people and expel it as a black cloud of flies to Percy's disastrous scheme to torture Delacroix in his final moments, "The Green Mile" builds to a level of gothic intensity that mirrors the feeling of King's fiction at its most spellbinding. Even if the story loses some momentum in its drawn-out denouement, the inexorable fate that ties Paul and Coffey together left the audience around me sobbing. Like the best supernatural stories, "The Green Mile" presents us with the darkest questions of human life in outlandish and paradoxical form. For Darabont and King, the Green Mile is a metaphorical vision of the world, where we all wait for our names to be called. It matters how we behave while we're there, but it's hard to say why, since we're all guilty of something and we're all leaving the same way.

Shares